Some things never change

Never trust a dog to watch your food.

—

Patrick, age 10

Our country has witnessed sweeping changes—from the untamed wild times of Buffalo Bill to the techno-

logical era of Bill Gates—but food has never lost its central role in our lives. Food not only sustains life but also

enriches us in many ways. It warms us on cold, dreary days, entices us with its many aromas, and provides end-

less variety to the everyday world. Food is also woven into the fabric of our Nation, our culture, our insti-

tutions, and our families. Food is on the scene when we celebrate and when we mourn. We use it for

camaraderie, as a gift, and as a reward (and sometimes as a crutch).

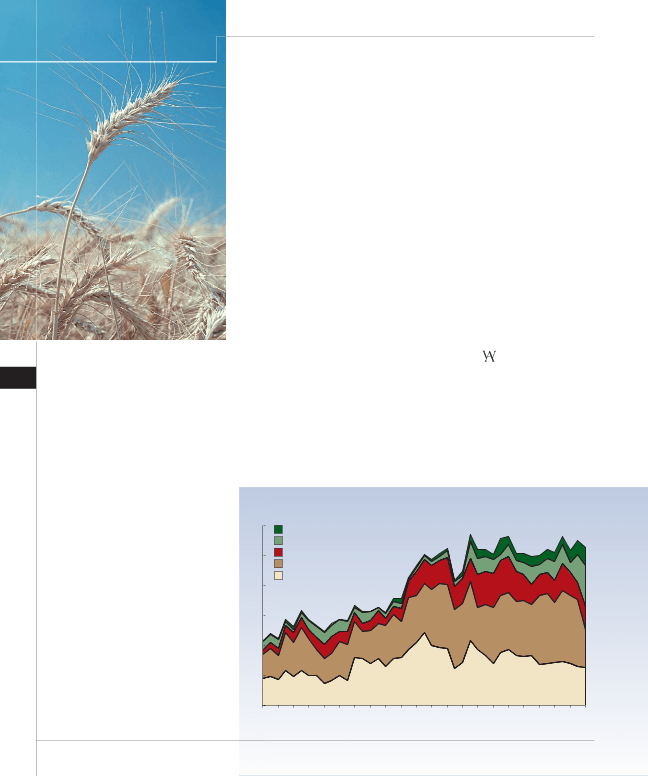

We are all aware of how food has changed. At the turn of the 20

th

century, home cooking

and canning were fixtures of life in America. Lard, seasonal vegetables, potatoes, and fresh

meats were the staples of our diet. And 40 percent of Americans lived on farms. Today, con-

venience foods and dining out are common. Ethnic diversity has influenced our tastes

and the variety of foods available. Technology and trade allow us to enjoy most foods all

year round. And only 1 percent of the population grows our food, while 9 percent are

involved in the food system in some way—in processing, wholesaling, retailing, serv-

ice, marketing, and inspection.

What Americans often forget, however, is the remarkable system that delivers

to us the most abundant, reasonably priced, and safest food in the world. The

American food system—from the farmer to the consumer—is a series of intercon-

nected parts. The farmer produces the food, the processors work their magic, and

the wholesalers and retailers deliver the products to consumers, whose choices

send market signals back through the system. Every piece fits every other piece,

notwithstanding an occasional gap and pinch. Our mission at the Economic

Research Service (ERS) is to understand this system and effectively communicate

our findings to the players in the system.

Some of those gaps and pinches currently receiving ERS scrutiny include

obesity and food choices, the need for better targeting of food assistance benefits,

as well as the environmental impacts of agriculture. The challenges of biotech

foods and of emerging global markets and competitors (including Brazil, China, and

Ukraine) are also among the issues analyzed by ERS.

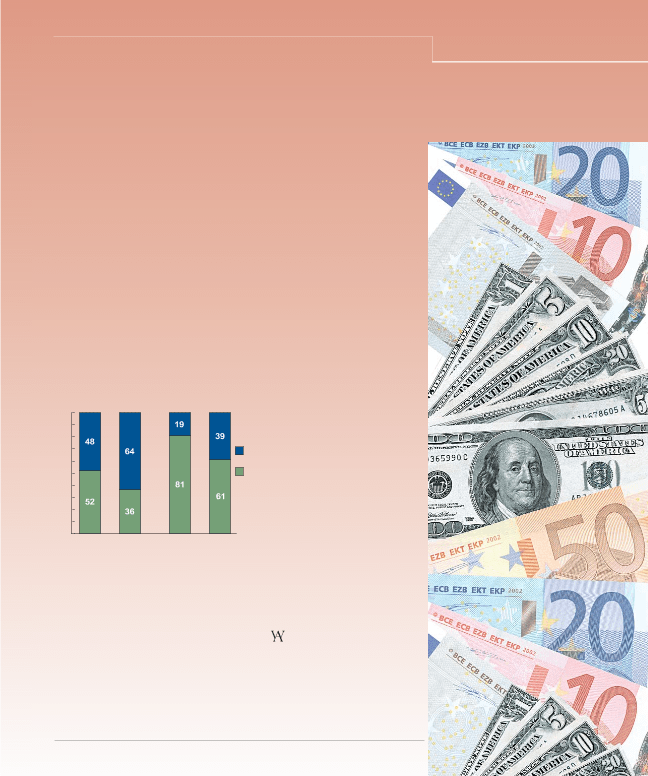

At the end of the day, it is safe to say the U.S. food system has done a remarkable

job of using technology and inventiveness to its advantage and ultimately to the benefit

of the consumer. We get the foods we want, when we want them, in the form we want

them, all at affordable prices. Thanks to this system, Americans spend less of their income

on food than do consumers anywhere else in the world.

Despite the dramatic evolution of the American food system, there are some constants in

our ever-changing world. Americans will always love food. The American food system will continue

to adapt, grow, and provide us with the products we desire. And yes, that timeless advice stands:

Never trust a dog to watch your food.

James R. Blaylock, Associate Director

Food and Rural Economics Division, ERS